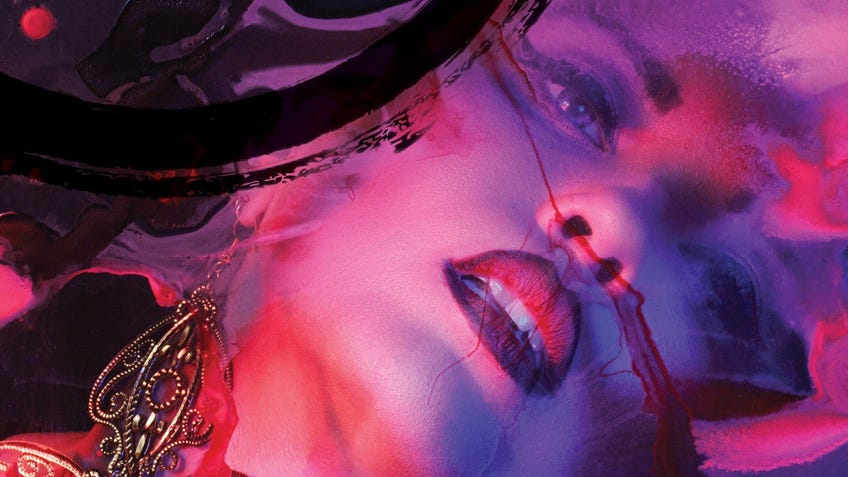

I was a bisexual teen bloodsucker: how Vampire: The Masquerade saved me from early-2000s homophobia

A monstrous supernatural hunter gave me the space and security to, in some weird way, be myself.

Of all the years of my life, 2000 stands out particularly vividly in my memory. It was the year I turned 15, the year I got my first mobile phone. The glorious mechanical violence of Robot Wars was must-see TV for young nerds, and the sugar-coated strains of Britney Spears’ Oops, I Did It Again were un-flipping-escapable.

Above all, though, it was the year I discovered Vampire: The Masquerade.

As a die-hard Warhammer kid, I was peripherally aware of the concept of tabletop roleplaying games. I knew folks who played Dungeons & Dragons, but to my untrained eye it seemed to revolve largely around doing maths and looking up information in sprawling, complex tables - like someone had taken the fantasy adventure archetype and smothered it in a layer of pure homework.

V:TM was different, though. From the moment I laid eyes on its green marble cover in my local game shop, it seemed to exert a kind of mesmeric hold over me. Flipping through its pages, I was drawn to its edgy black-and-white illustrations, its unflinchingly dark tone and its tantalising central premise: that just beneath our daylight world lurked something old and strong and dangerous.

Feeding in Vampire: The Masquerade came laden with not-so-subtle sexual connotations.

Where D&D cast players as fearless heroes battling a menagerie of monsters, Vampire: The Masquerade was much more morally ambiguous. It let players assume the role of undead predators, eking out their existence by drinking human blood. In its shadowy mirror image of the modern world, vampires were the descendants of Cain, the biblical first murderer. Eternally cursed by their forefather’s crime, they spent the centuries hiding from the sun, evading torch-wielding puritan mobs and hatching sinister machinations to secretly control mortal society.

It was a chaotic mish-mash of blood-spattered horror movie imagery, paranoid conspiracy theory and fire-and-brimstone religious terror, and it instantly grabbed me by the throat. As an added enticement, it wasn’t shy about sex and violence. What more could any adolescent boy ask for?

I threw myself into the RPG and its fictional backdrop with gusto, cajoling my goth pals into forming a semi-regular game group. I snapped up sourcebooks and novels and threw myself into my newfound obsession. But in other respects, 2000 was a tough time in my life.

In my native Scotland, a debate was raging over a homophobic law which forbade the “promotion” of same-sex relationships in schools. The newly devolved Scottish parliament was working to repeal the legislation, but the attempt had sparked fury among social conservatives and some religious groups. With the support of a millionaire transport tycoon, they launched a backlash against the terrifying idea of extending basic respect to LGBT+ people. Billboards sprung up across the country warning of the potential dangers to impressionable schoolchildren. Ridiculous tabloid headlines screamed about “gay sex lessons for Scots tots”. Hatred and bigotry became part of mainstream public discourse.

As a bisexual teen, it created a toxic and terrifying environment at a time when I was still figuring out my identity. It was impossible not to take some of the vitriol on board, and to see my sexuality as something to be ashamed of.

What I didn’t realise at the time was just how important Vampire: The Masquerade would be in throwing me a lifeline.

Roleplaying gave me the chance to say and do things that felt impossible in real life.

My regular character was a member of the Toreador vampire clan, a group of unabashed hedonists who spent their unlives in pursuit of aesthetic and artistic pleasure. While his clan brethren tended to favour highbrow forms of expression like painting or sculpture, he was a prog-metal guitar god, thrilling audiences with complex riffs and pretentious, widdly solos.

He was also, with hindsight, bi as hell, sneaking out after shows to feast on the blood of male and female fans.

Feeding in Vampire: The Masquerade came laden with not-so-subtle sexual connotations. The roleplaying game devoted pages of breathless text to describing the passion and euphoria of drinking blood. Its accompanying fiction was full of seduction, attraction and longing. And just in case anyone was left in any doubt, it referred to the vampire’s bite as “The Kiss”.

Looking back, it seems embarrassingly overblown - like a Mills & Boon romance novel with black eyeliner and a Sisters of Mercy soundtrack. But the game provided me with a chance to play out intense scenes of physical intimacy with male and female characters. In doing so, it slotted neatly into a long-established tradition of using creatures of the night to explore teenage sexuality - from the lesbian overtones of 1872’s Carmilla to the soap-opera relationship drama of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Unlike novels, movies or television, though, Vampire: The Masquerade didn’t relegate me to the status of a passive observer. Roleplaying gave me the chance to emotionally inhabit a character, and to say and do things that felt impossible in real life. That level of immersion and agency is unique to games, and as improbable as it seems, the proxy of a monstrous supernatural hunter gave me the space and security to, in some weird way, be myself.

All of this stuck with me long after I’d moved on from the RPG, when work, bills and parental responsibilities made weekly roleplaying sessions a dim and distant memory. So it came as a blow when Vampire’s most recent edition used real-world atrocities against gay and bisexual men in Chechnya as material for one of its in-game storylines. Its clumsy, dismissive, insensitive handling of the imprisonment, torture and murder of innocent people sparked outrage online, forcing its publisher to apologise.

Nowadays there’s a community of indie LGBT+ RPG creators providing some brilliant alternatives. My favourite, Monsterhearts by Canadian designer Avery Alder, puts players in the shoes of vampires, werewolves and witches in the most terrifying setting imaginable: high school. It’s fiercely queer, and it unflinchingly deals with ideas around relationships and sexual orientation. And, of course, it still makes plenty of room for chills, spills and mortal terror.