Tabletop RPG Emet captures the powerful shared experience of being Jewish with humour and tragedy

Exploring one of the titles in Jewish roleplaying anthology Doikayt.

The thing about gathering a couple Jewish folks together to play two or three tabletop roleplaying games is that it’s a setup for failure.

It’s like planning to pop down to the bagel place and the grocery store, but you see Mrs. Rossenstein from down the street in line at the bagel shop and she asks about your job, how’s your dad doing, is the cat still alive, and you get a dinner invitation. When you do finally leave, nearly two hours have passed and you don’t want to go to the grocery store anymore. If it’s not obvious, we talk a lot.

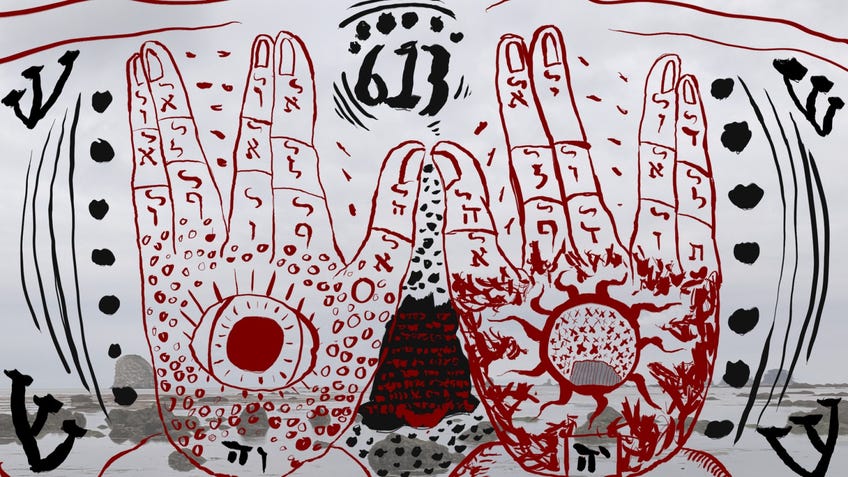

I invited a few folks to play some games from Doikayt: A Jewish TTRPG Anthology on a Friday night. Doikayt is a crowdfunded collection of tabletop roleplaying games by Jewish designers and illustrators packed full of games reflecting different expressions of Judaism.

We anticipated playing Emet by Evan Saft, Lunch Rush by Nora Katz and Christmas Day by Eli Seitz. Lunch Rush is a DM (Delimaster) guided RPG where the players work in a chaotic Zagat-rated Jewish delicatessen, hallowed community cornerstones, catering to all sorts of colorful customers with unrealistic demands. Christmas Day is a freeform LARP of the Cohen family’s yearly Christmas dinner at a tiny Cantonese restaurant in Manhattan. It’s the only place still open and players air and process familial grievances after a long month of being reminded by nonstop Christmas commercialism that Jews will always be different. It became clear after several minutes of derailed conversations just one game was in the cards for the evening, so we settled on Emet.

The game facilitates the creation and storytelling process with questions akin to the Mah Nishtanah asked at Passover.

Emet is a GM-less storytelling game where the players are Golem created to protect a collaboratively-designed community. The Golem see the community through five acts, marked by problems which increase in severity and how the community changes over time. Because Golem are created, not born, each player decides the Golem’s commandment for another player. The Golem must act within the commandment’s specific parameters.

The game facilitates the creation and storytelling process with questions akin to the Mah Nishtanah, the Four Questions, asked at Passover. How is this night different from other nights? How do we Golem approach this problem?

Cantor, a heavy-handed Jew-ification of the fictional island of Catan, was our desert community, settled on the banks of an oasis. Cantor had a deli, a Jewish Community Centre with an extensive darkroom facility, a theatre, a towering agency building, a tiny synagogue attached to a humongous comedy club, housing, a salmon farm, law and med schools, and a Judaica store.

Our shared cultural experience as New York metropolitan area Ashkenazi Jews led us to make essentially the Upper Westside in the middle of a desert. The socialist utopia of Cantor had two career options: photographer or comedian, but still had law and med schools so mothers would have something to brag about.

The commandments of our Golem were: tend the salmon farm, usher the theatre and fight for the agency’s in-house bagel shop.

We knew we had to be goofy from the get-go because the game only got heavier from there on out. But that’s how Jews have always coped; Jewish folks have to combine laughter with tragedy or else we’d never get over our generational trauma. After all, like they say in Cantor, “We don’t need doctors, we have a comedy club. Because laughter is the best medicine.”

Jewish folks have to combine laughter with tragedy or else we’d never get over our generational trauma.

The tumultuous history of Cantor was punctuated with vandalism, violence, illness and natural disaster. The Golem defeated the vandals by drowning them in the salmon farm. Violence culminated in a targeted attack on our agora-like downtown area. Illness manifested in a mass hysteria dancing plague affecting the youth population. The community wrote a successful musical about the event. Our oasis began to dry up and sacrifices were made.

We kept telling an inherently Jewish story, despite trying to lean away from it at times. Still, Cantor had its own Kristallnacht. The community bounced back from illness with resilience and a musical. Jews always create in reaction to tragedy.

It came time for the final act. The final problem presented by Emet is extermination. An outside community decides you are to be blamed for all of their issues. Their only solution? To get rid of your community. The game ends if and when the Golem stops the extermination. The way Emet presents the questions is haunting: “Is this enough to stop them?” “Is this the end?”

It wasn’t enough. The Golem answered “Yes” to “Is this the end?” A quiet passed over us as we grappled with the somberness and hopelessness of the situation. This wasn’t just an in-game scene. Extermination has never been a hypothetical.

We thought we offset the inevitable ending with our humour, however it just made it hit harder. No matter how fiercely we fought back with our love and our laughter, it wasn’t enough.

To the untrained goy eye, Emet is a game free of overtly religious themes. But it’s distinctly Jewish. Judaism is all about questioning. You are not told the answer, you yourself give it. The problems presented are all problems Jewish people have survived over the course of millennia.

In true Jew fashion, our cooperative overlapping style of conversation led us to approximately an hour of gameplay and two hours of sidebars. Those side conversations were just as important to the gameplay as the storytelling was. We shared our trauma, the schoolyard anti-semitism and, at least in my case, the time a past partner’s mother called me the anti-Christ because I am Jewish. “I got therapy three times this week instead of twice,” was quipped. The shared realisation that taking darkroom photography classes is such a Jew-y thing to do was hysterical.

The problems presented in Emet are all problems Jewish people have survived over the course of millennia.

To play Emet with other Jews on Shabbos was a gift. We all processed a lot. It was an honest moment of catharsis.

Even though Cantor faced extermination, we as the players continue on with a new shared story. Jews have always faced death head on. Brutal monarchies and fascist governments come and go, but we’re still here. We keep our traditions alive by sharing our survival stories on our holidays. (It’s common to joke that our holidays are about someone trying to kill us but we survived.)

All of this is to continually remind us of where we’ve come from and how we got to where we are. The Exodus, the ghettos, the pogroms, the Holocaust. They’ve tried everything to get rid of us and yet here we are. Still laughing, still telling our stories, still eating pastrami on rye. Survival is in our genetic makeup.

After all, living is our best revenge.

Doikayt: A Jewish TTRPG Anthology is available now in a physical edition or digital download on Itch.io.