Why does everyone hate Monopoly? The secret history behind the world’s biggest board game

Chance encounter.

Tabletop games have come a long way since the 1930s when the Parker Brothers first unleashed the game of Monopoly onto the world. We’ve seen massive innovations in play and design across the industry, whole new genres lift their heads from the primordial soup and designs that would literally not have been possible at the time Monopoly was first published.

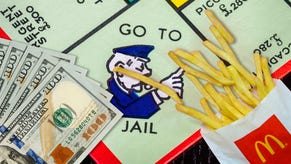

Board games, and everything related to them, are better now than they have ever been. And yet, to this day, Monopoly is still one of the largest board games in the world - available in 37 different languages in toy and book shops the world over. If you want an example of just how omnipresent it is, there’s even a McDonald's Monopoly promotion.

If you say you’re into board games, it’s not unlikely someone will assume you spend your nights playing Monopoly with your mates. But that couldn’t be further from the truth. Despite its mainstream appeal, ask most big board game fans if they want to play a game of Monopoly and they’ll likely roll their eyes or grimace at the mere suggestion. So why is that? What’s so bad about Monopoly? Why does it harbor so much disdain? Well, it’s a complicated thing to explain. To start we’re going to have to go all the way back to 1903 - to when Monopoly was known by an entirely different name.

Elizabeth Magie was an American game designer, writer and inventor born in Illinois in 1866. Born to newspaper publisher and abolitionist James K. Magie, who would spend the 1850s accompanying Abraham Lincoln during the Lincoln-Douglas debates around Illinois, Elizabeth was no stranger to progressive politics from an early age.

Magie was somewhat of a jack of all trades, dipping her toes into all sorts of pastimes and professions, from poetry, comedy and theatre to engineering. In fact, at the age of just 26, Maggie received a patent for an invention of her own design that eased the process of typewriting, something she was intimately familiar with due to her time as a stenographer in the early 1880s. This was a time where women were credited with less than 1% of all patents filed.

Magie was looking for an effective way to espouse the virtues of Georgism. It was ultimately game design that would take her focus.

She was a woman that believed in equality, a staunch feminist and political activist, as well as a believer in the principles of Georgism - the economic ideology developed from the writings of Henry George that was popular among some political theorists of the time. Georgists believe that instead of the standard method of taxation where a percentage is taken from income or capital or whatever source that comes straight from the work of those producing value in the economy, there should instead be a universal land tax that increases or decreases based on the usefulness, size and location of owned land in the state.

Bear in mind that this is a time where land ownership was basically the entirety of economic value in the country. The US was in a place where if you owned land you were sorted - and if you didn’t you were at the whims of whoever owned the land you were on.

In general, Americans weren’t massive fans of being taxed. Georgism wanted to tax the value of the land itself across the country to fund the American government, after which any leftover funds could then be equally and fairly distributed among the citizens of the state. This was a pretty enticing system for a lot of progressive political leaders because it was seen to motivate land cultivation, it put money in the hands of those who had low socioeconomic standing and it got rid of the idea that landowners and landlords held all the power of the land that citizens used despite not really contributing to anything that was made on that land.

Magie was a big believer in Georgism, and she wasn’t the type of person to keep her beliefs to herself. When she was working as stenographer she was making a measly wage that she had no way of supporting herself on without marrying a man and becoming a kept woman. In protest of this, she posted a newspaper advertisement trying to auction herself off as a “Young woman American slave” looking for a husband who could own her. She wanted to show people the position that women across the world were in at the time, stating quite openly that the only people who were truly free in the United States were white men.

Not being one to keep quiet about her political beliefs, Magie was looking for an effective way to espouse the virtues of Georgism. It could have been any of her multitude of talents that she leaned on to bring home the message, but it was ultimately game design that would take her focus. In 1903 Magie applied for a patent for what was to then be known as The Landlord’s Game, the patent later being granted in 1904.

The Landlord’s Game takes place on a strikingly familiar board. The players move around a track taking ownership of properties and charging rent on those that land on them. The board game was originally designed to demonstrate how much damage a system that allows the monopoly of land ownership can cause and highlight how some of that damage can be avoided with the use of land value tax as Georgism dictates.

The Landlord’s Game existed in two separate versions. The first was essentially modern-day Monopoly.

The Landlord’s Game existed in two separate versions. The first was essentially modern-day Monopoly. The players moved around the board, swallowing up every space worth of property they could and slowly grinding the other players down to the point where they were forced to sell their own lands, with the winner being whoever ended up with everything at the end. This was the version that players would first be introduced to and was supposed to represent the then-current system that Americans were living under.

The goal was to try and show just how horrible a system like this was for everyone but the person who ends up with the monopoly. This was especially effective on children, who are acutely aware of when they’re being treated unfairly which would hopefully make them more aware of that unfair treatment as they grew older and entered the workforce. (Fun fact: injustice is one of the earliest concepts a child’s brain forms in their development.)

Once the players had been subjected to the drudgery of the first version of the game, Magie would then introduce a second version of The Landlord’s Game that instead followed Georgist principles. The anti-monopolist, Georgist version of the game not only showed that land tax would stop one person running away with everything and leaving all the other players destitute at the end, it also had a more cooperative end goal - the win-state being when the player with the lowest monetary amount had double their original stake.

If it’s not clear already, The Landlord’s Game is the Monopoly that we all know today. But there’s a good chance you may never have heard of Elizabeth Magie before today. She’s not credited as the original designer, and until the 1970s her design was almost entirely lost to the public eye. But how did this happen?

Enter a man named Charles Darrow. After a pleasant meal with his friend and Philadelphia businessman Charles Todd in 1932, the two Charles’ sat down with their wives to play a copy of Magie’s game that Todd had recently learned. The Landlord’s Game was not a massive commercial success; most of the copies that existed were just unlabelled boxes of components passed from friend to friend. In fact, it’s unlikely that the players even knew the official name of the game as it was more commonly referred to as ‘The Monopoly Game’. There was no official rulebook, no place where you could feasibly purchase a copy of the game - it was just something you were taught.

It was Darrow's version of Magie’s original ruleset that was sold to the Parker Brothers and became the blockbuster hit we know it as today.

It perplexed Todd, then, when Darrow asked him to write down a copy of the full rules for the game they had played after many an evening spent in revelry. It was even more strange when Darrow claimed to have emerged from his basement, struck by inspiration for a brand new board game under the name of ‘Monopoly’ that he seemingly invented all on his own. It was this bastardised version of Magie’s original ruleset that was then sold to the Parker Brothers and became the blockbuster hit that we know it as today.

Monopoly’s success led to Darrow and the Parker Brothers making a shedload of money, while Magie made around $500 - with no royalties - from the Parker Brothers’ purchase of the Landlord’s Game patent and two of her other titles. The sum was so little that she couldn’t even recuperate the costs of the original game’s patents and fees. To make it even more egregious, there’s supposedly a typo that was made on the original board of The Landlord’s Game that Darrow hadn’t even fixed when he brought out his own version.

Monopoly’s history hardly lays a great foundation for the classic, not morally anyway, but what does it have to do with the game itself? And if the story of Magie and Darrow isn’t very well-known, then what does it have to do with the apparently universal hatred towards Monopoly?

Well, for one, despite it maybe seeming quite novel at the time - Magie’s original patent for The Landlord’s Game was supposedly the first game board to feature a continuous looping path - the game itself isn’t designed to be fun. It’s designed to make a statement. While one player around the table might be flying high as they squeeze every cent out of their competitors, the rest of the people playing will be subjugated to a long slog of slowly going bankrupt with not much they can do about it. But that’s the whole point. Magie wanted players to feel like they’d been cheated and unfairly cast asunder, so that when she brought out the second, Georgist version of the game that showed the virtues of her cause they’d implant themselves in its philosophy even further.

The natural human drive for competition might have left the more cooperative second version of the game out of the limelight when Darrow and the Parker Brothers brought the idea to the masses, but without it Monopoly is just a game that was literally designed to make you frustrated. Without the “Let’s take a look at what you could have won” reveal at the end, you just have 75% of the players cursing their luck after the game. And, let’s be honest, it is a game of luck.

There’s a common trend in some board game circles where a game will be rated on a scale of how luck-based it is. There's a good reason for this that’s not just players being sore losers, I promise. The scale offers an insight to how much agency the player has when they sit down to a game. Games of absolute pure luck, such as a roulette wheel, might offer the illusion of choice - the big table of different bet options you can take, for example - but even the most savvy gamblers are still at the whims of the spin. If you’re betting on red and it comes up black every time, then you’ve lost money. You didn’t necessarily do anything wrong, luck just didn’t go your way. For an even better example, if you were just betting on a coin toss would you feel like you were in control of the outcome?

Monopoly is so far slanted toward random chance of the scale that player agency is almost non-existent.

On the opposite end of the spectrum you might have a game like chess or draughts. There’s no random chance, both players start with the exact same set up of pieces and there’s not a dice roll in sight. Every move you make is up to you; if you fail it’s because of your moves and your opponent’s actions throughout the course of the game, not because of a throw of the dice or the spin of a wheel.

The problem with no chance is that the games can get quite dull and predictable; you can’t make a move in chess without it already having its own name and thesis paper attached. The trick for many games is finding the balance between these two ideals that match the experience they’re trying to create. Bits of luck or randomisation will change up the playing field for the players, keeping things fresh and exciting, but if too much luck is involved then players can get frustrated as they seemingly lose games where they’ve made all the right moves. Player agency - feeling like the state of the board is directly affected by your actions - is important. Without it, you may as well just be watching the spin of a roulette wheel.

When it comes to Monopoly, the game is so far slanted toward random chance of the scale that player agency is almost non-existent. The players have a maximum of two situations in which they can make a meaningful choice: when they’re asked to pay for something or when they can trade with other players. Do you want to buy the property you landed on? The answer is almost always yes, because you only win the game by buying properties. The only real reason you wouldn’t buy one is to save for another that you might not even land on - and if you don’t buy it, it lets everyone else around the board auction it off for potentially even cheaper. So, if you’ve got the money, why wouldn’t you?

Remember that this is only a choice for about half the game, too. Once all the properties are gone you can only acquire them through deals made with other players - which usually amount to “I’ll finish your set if you finish mine” - or through someone going bankrupt. You could point out the houses and hotels, and that you have the option to put them where you like so there’s strategy in where you place them, but again, you can choose what number you bet on on a roulette table. It doesn’t mean you’re changing the outcome.

This aspect is one of the key reasons why Monopoly can be so frustrating to play - and why many people end up hating the experience. It was never meant to be fun for anyone but the winner, and even then it’s slow, unforgiving and your options are so limited they might as well be non-existent.

Okay, so it’s not a great game. It’s old and clunky, and may be better suited to kids than to adults, but so are a lot of board games. Is Monopoly really that more deserving of all this hatred than any of the other classic board games that have existed for over a century?

Not all of the argument against Monopoly comes down to the game itself. Despite it being the very thing that Elizabeth Magie was trying to warn against with her design, Monopoly’s publisher and rights owner Hasbro has a bit of a monopoly on the tabletop market itself. It might be difficult to reconcile when you look at Hasbro as a company - the people who make Connect 4 and Trivial Pursuit, Cluedo and Monopoly - but it’s an absolutely massive fish in a small pond.

The inventor of The Landlord’s Game continues to see no credit for her role in designing Monopoly.

Dungeons & Dragons has an absolute stranglehold on the RPG market in most parts of the world. Magic: The Gathering isn’t doing half bad in the trading card game market, either. Guess who owns Wizards of the Coast, the makers of both of those properties? That’s right: Hasbro. At the time of writing, Fortune 500 estimates the market value of Hasbro to be around $13 billion.

It’s difficult to avoid Hasbro’s presence in the toys and games space. If you see a toy for Marvel, Disney, Transformers, Star Wars, Nerf or My Little Pony you’ll see a Hasbro logo on the corner of the box. When a company has that much reach, and that many contacts, it’s difficult to avoid.

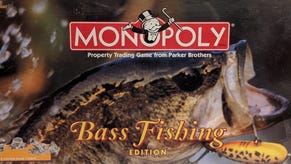

Almost every month there seems to be a new edition of Monopoly that’s basically just the same game with a different brand slapped on top. Marvel, Star Wars, Rick & Morty, Warhammer 40,000 - it’s never-ending. Not to mention the cringe-inducing Monopoly for Millennials and Monopoly: Socialism, which have about all the nuance you’d expect. The socialist edition of Monopoly already exists, Hasbro. It's called The Landlord’s Game by Elizabeth Magie. Yet, according to the Washington Post, upon the release of a version of Monopoly celebrating great female figures, Ms. Monopoly, the famed feminist, political activist and original patent holder and inventor of The Landlord’s Game continued to see no credit for her role in designing Monopoly.

If you like Monopoly, more power to you. No-one should shame you for enjoying something. But if you’re at a gathering of family and friends deciding on a game to play and someone suggests Monopoly, you might notice someone around the table roll their eyes or grimace at the suggestion. And honestly? They’ve probably got their reasons.

Whether it’s the mistreatment of the original designer, the staunch pro-capitalist themes its modern-day iteration carries or even just the design of the game itself, Monopoly can be a pretty difficult game to stomach losing an evening to. So maybe consider giving something else a try.