What can board game Pandemic teach us about the real thing? We played with a disease expert to find out

Cardboard versus reality.

The world has been a very confusing place recently. Finding ourselves in the midst of the global coronavirus pandemic, it’s been tough to comprehend the enormity of the situation unfolding before us. Our evolving understanding of a novel disease, coupled with mixed messaging and downright misinformation has made it hard to understand what is happening.

As strange as it sounds, could a board game help? Pre-lockdown, I sought to find out over a game of Pandemic with disease control expert and senior lecturer on epidemiology at Newcastle University, Dr Mark Booth.

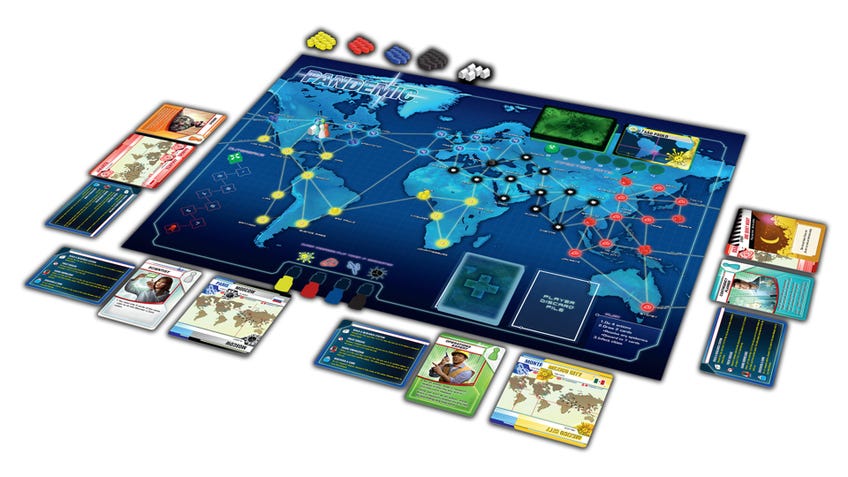

Pandemic is the creation of designer Matt Leacock and charts the progress of four infectious diseases spreading around the world. In the co-op game, each player is assigned a role and must use their character’s unique abilities to eradicate disease cubes and find a cure. To do so, they move around the board, performing various actions that work toward containing the diseases. At the end of each turn they must draw from a player deck. All being well, these cards help them in their quest for a cure. They then draw from an infection deck that directs players to place additional disease cubes onto the board. Every so often an epidemic card will be drawn from the player deck and all hell breaks loose: a new hotspot receives three disease cubes and the discarded infection cards are shuffled back into the deck to be later drawn again, intensifying already infected locations.

The idea of intensifying an already affected place was not unrealistic.

Things did not start well in our first game. After only a handful of turns, an early epidemic card plus some very unlucky draws meant that within a short period of time, things had spiralled out of control and we were defeated.

Although Booth was disappointed to lose, he drew a parallel between the board game and the real-life spread of infections: “I liked the epidemic card. It demonstrates how quickly an infection can get out of control. I also thought the idea of intensifying an already affected place was not unrealistic.”

Our second playthrough went much better. We quickly got on top of a developing situation in North America before eradicating an outbreak of black cubes in the Middle East. Southeast Asia was a different story, as we struggled to contain outbreak after outbreak. The same cities kept reappearing through the infection cards, leading to the diseases’ constant return.

“This concept of secondary outbreaks is not a bad one,” Booth explained. “There are a number of real-life examples where an infection has been cured only for it to return. Take, for example, Malaria; drug resistance in many parts of the world meant that programmes stopped working and the disease came back.”

The idea that different strains would be contained in one area is completely unrealistic.

After eventually overcoming the outbreak and curing all four diseases for victory, I asked Booth how Pandemic stands up to a real public health crisis.

“Well, the first thing to note,” he said, “is that the diseases themselves are very abstracted. The idea that different strains would be contained in one area is completely unrealistic. For a disease to be truly pandemic, it must go beyond borders. What we actually have here is a series of regional epidemics.”

The idea of quarantine doesn’t appear much in the game. This is an absolute cornerstone of public health.

While Pandemic does feature a quarantine specialist player role able to prevent disease cube outbreaks in nearby cities, the idea of quarantining regions is a concept explored to a much greater extent in Pandemic Legacy, the campaign-based series of board games co-designed by Leacock that see the impact of infections have a permanent effect on the world’s state. Booth was reassured to hear that quarantine features much more prominently in the later release, criticising its reduced importance in the original game.

“I noticed that the idea of quarantine doesn’t appear much in the game,” he said. “This is an absolute cornerstone of public health. As we know from the coronavirus, you need to quarantine people quickly to stop the infection from spreading. The Ebola virus, for example, was contained effectively through a series of ring-fenced vaccinations.”

As for Pandemic’s cast of player characters, including a researcher, medic and scientist, Booth similarly noted key differences from reality: “While the idea of global travel is relevant, it would be populations moving around rather than doctors or researchers.”

Booth began to move cubes around the board to demonstrate his point.

“There’s also no policy specialist. They often have the biggest role to play deciding what resources go where. Their ability to get governments cooperating with each other is essential in controlling a pandemic.”

The board game is a little too abstract and the principles are a little mashed up.

So, would Booth consider using Pandemic to explain the basics of epidemiology? “No,” is his unequivocal answer. “It’s a little too abstract and the principles are a little mashed up. Some of the cornerstones of public health are missing and the dynamics that affect how you control an outbreak aren’t quite right.”

Pandemic's global perspective and explosive gameplay gives us a general sense of how diseases spread. Ultimately though, there's still much missing - not least the real human cost to the people who are affected. While a board game can simulate events using an abstract system, the same cannot be said for the real world. Playing board games like Pandemic can help us get a sense of the process, but the real thing is much more serious and complex.