Swedish kid melange: how Martin Takaichi designed Tales from the Loop’s board game from his own childhood

Deep in the Swedes.

Free League’s decision to create a board game based on Tales from the Loop, one of its more popular tabletop RPG worlds, was surprising for a few reasons. The Swedish publisher had only dipped its toes into board games once before with 2019’s adaptation of strategy video game Crusader Kings 3, and while this newer crowdfunding campaign showed a lot of public interest, the path from telling stories about “the 80s that never was” to a more rules-bounded experience wasn’t totally clear.

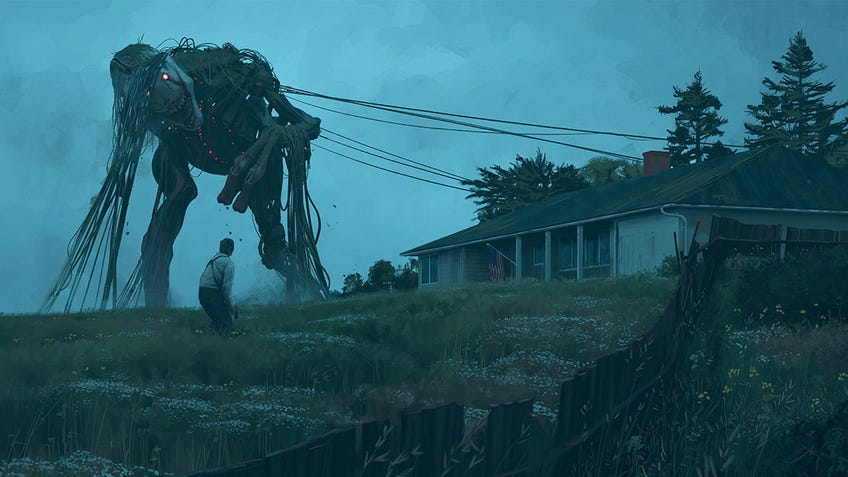

The results of that 2020 Kickstarter campaign, Tales from the Loop: The Board Game, sees players control one of several school-age children living in the suburban Mälaren Islands and under the shadow of The Loop, a colloquial name for the nearby and secretive research facility. Using only their wits and small possessions, they must sniff out the mysteries suffusing their home and its surrounding woods - including rogue robots and time-displaced dinosaurs - by travelling between locations and gathering clues, all while making sure to return home before curfew and completing their chores.

Dicebreaker sat down with lead designer Martin Takaichi to discuss the process of transforming a freeform RPG into a collaborative board game, drawing on his own memories of growing up near the Mälaren Islands and the influence of trippy 80s children’s television on the finished product.

How did you decide Tales from the Loop should be adapted into a board game?

We tend to talk about the different games or different IPs that Free League is working with or [the publisher’s] own creations. We had been discussing that it would be fun to make some board games based on the roleplaying games that we have, and I was like, ‘Yeah, maybe Tales from the Loop would be a good one to get started on.’ Then they said, ‘Okay, let's do it. You should do it.’ [laughs] Well, okay, then. So, they kind of roped me in there.

During design, I thought, how do I even emulate the kind of feeling when you're a kid? I can't just bike around the neighbourhood and do ping pong bash on people's doors and steal apples.

Even though Tales from the Loop might not be my favourite bit of Free League lore, it is still very, very close to my heart. I live not far from where it took place, basically. I'll just use my own experience growing up, and pool all of that with Simon [Stålenhag]'s experience as well. And just, you know, put it in board game format.

Did you approach the design from a top-down perspective using the established world and lore, or did the mechanics come first?

Something I keep coming back to when designing games is that the mechanics really kind of drive it. But if the mechanics feel disconnected, it's just this pretty thing. It's just an abstract. So, no, it was top-down from the start, as you said. We need to make something that really feels like it fits the world. Before we started working on this actual game, we had quite a few discussions about what kind of game we should make. We should make something like an RPG, I guess, but in a board game format. In the end, we wanted the kind of Kids on Bikes experience, Stranger Things or what have you.

It's very interesting that you said you were of that age and grew up relatively close to where The Loop is supposed to be.

I mean, I just take the bus [from] here for 10 minutes.

In addition to that personal familiarity, what other media did you and the team look at to inform the design?

A few of our touchstones work internationally and are pretty much universal. Everyone’s like ‘The Goonies? Yeah. Stranger Things? Yeah, we know those.’ So, besides personal experience as a kid it’s also a lot of old Swedish TV shows and things that echo those. We wanted to keep a little bit of that because it should still feel a little bit like Sweden, you know? A lot of easter eggs I put into the game to just be like Sweden.

When thinking about making a new game, I tend to find it easy to just take mechanics that work in other games and just mash them together.

Can you talk a little bit more about like these Swedish shows that informed the design, especially if an international audience wouldn’t recognise them?

Well, yeah, there's quite a few. [laughs] Although I remember watching all these shows as a kid, they kind of blend that into this strange, Swedish kid melange of different things. I can’t remember the name, but it involved a teddy bear or plushie. It was very much like a kid going around on cheap sets or in the woods and having crazy adventures. Those kinds of feelings when you just think back, you want to capture a little bit of that weird, strange time.

Do you think the team was successful at instilling that sense of mystery and background radiation of weird kids’ show into how the game feels when it's played?

We're never gonna be able to capture it perfectly, but I think we managed to at least get the kind of feel. Like when you move around the board, and there are strange things happening. It kind of feels like it doesn't really make sense and is slightly absurd in certain parts. You should be able to pull a thread and understand what's going on, but it's slightly off kilter. That's a little bit of the sense that I was going for.

Simon’s work and the Tales from the Loop RPG both do a great job of balancing mundane life against this otherworldly weirdness. How did you find that balance in the board game?

Some of these kinds of games quite often can get to a point where you should obviously do this, you should always do that because it gives us the highest percentage of success. And that feels like the antithesis to the kind of game that we want.

We knew from the start that it can't just be wacky adventures with robots. It has to also connect to the mundane. Number one was the structure of the game. If I'm a 12-year-old what does my day look like? I'm going to go to school - that's number one. Then, I might have some time between school and going home to have dinner. What can I do in that free time? What if I have a bike? What if I have a bus card? That was the first thing - you needed to go home for dinner and homework at the end, and you got to start at school. Of course, also, you have your little happiness meter for your parents.

We also tried to sprinkle a bit of normal things into every place. The school cards come up and some of them are, you know, very mundane, such as rinsing with your fluoride. But even the stranger ones usually bring in everyday adults, regulars. These adults are just kind of there in the game. Sometimes they can become an obstacle, but mostly they're not cognizant of what's going on. Zombies going about their daily lives.

I imagine it was difficult to create these mystery scenarios so that they enticed players enough to hook them without overwhelming certain groups through sheer difficulty.

Absolutely, yeah. The stories are fairly complex, so it's not only balancing, but making sure that some weird edge case didn't mean the scenario suddenly came to a grinding halt. Some, such as the suggested starting scenario, were designed to be easier, a bit more forgiving, while also introducing all the mechanics. When I started the design process, I wondered if we could make something in the Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective vein. That would be like almost bridging the RPG kind of gap there, right? But then I felt you could just as well play the RPG at that point. So, we dialled it back to more of a traditional cards and dice kind of game.

In that same vein, how then did you make failure interesting? This game uses dice and skill tests, which means failure is part of the equation.

We knew from the start that it can't just be wacky adventures with robots. It has to also connect to the mundane.

Some of these kinds of games quite often can get to a point where you should obviously do this, you should always do that because it gives us the highest percentage of success. And that feels like the antithesis to the kind of game that we want. We don't really want a Pandemic kind of game where you just calculate the odds. You should have a strategic discussion at the start of the turn but it shouldn’t always be hard and fast. Robinson Crusoe, for example, has a good design for giving players options - there's often three or four things that are all equally good. In our board game you should always feel like you're doing the right thing - or a right thing, maybe.

As for failure, we built in systems for players to manipulate the odds quite a bit. You can use your items or reroll dice by taking on conditions. Of course, another player can always help.If you spend some extra time, you can be pretty sure that you're going to succeed. Or ensure that you won't succeed at this and then ignore it. We want to give players a lot of decision-making power and also have them able to do what they feel is important without being necessarily detrimental to the group or the game.

What lessons or design elements of the Tales from the Loop RPG did the team study for this board game?

If you're not careful, you can feel like you're just designing a board for the RPG. Instead, you kind of have to pick the best pieces from the cake and take those. So, we kept the dice and we kept the push mechanic [on dice rolls]. Apart from that and the general theme, it was more about looking at locations and things we had already written for the adventure landscape of the RPG. That way, no matter which direction you come at both, some things will be familiar.

Free League is fairly new to the board game space. How was working with them on creating something beyond tabletop RPGs?

Although I remember watching all these shows as a kid, they kind of blend that into this strange, Swedish kid melange of different things.

It was a really good experience, and I believe they learned a lot as well. Since I was the board game guy, basically, and they were the RPG guys, they have a looser sense of rules. They're a bit more relaxed when it comes to things like that. It was towards the end of the development when I brought on Rickard Antroia, and he was going to develop a couple of scenarios for the game. He also loves board games, and in the process of making final adjustments and smoothing out any sharp edges, he kind of became my co-designer. It was really nice to have one more board game freak to bounce ideas with.

Speaking of Antroia, what other board games are present in the DNA of your adaptation of Tales from the Loop?

One thing that I thought was really clever from the third edition of Arkham Horror by Nikki Valens was the archive cards that had this choose-your-own-adventure style. That design became the core of our diary cards, which allow players to sort of construct their own stories for their characters.

When thinking about making a new game, I tend to find it easy to just take mechanics that work in other games and just mash them together. We had played a lot of Conan from Monolith just a couple years ago and were like, yeah, maybe we can have something similar regarding time. And those thoughts eventually became the method of representing time with cubes and slots on the character board.

The characters in the game are all children of different ages. How did you choose mechanics and create an experience that felt true to that framework?

That's actually an interesting question. Since you're paying kids, we don't want those scary horror game vibes - we want to keep it light. Conditions were a big one. I remember as a kid you just get tired now and then. You bike around all the time, then you just sit around and play video games for an hour, and then you're good to go again. Some of the chores are cool, but then you might have the worst cousin come visit and ask you to show them around town.

Something I keep coming back to when designing games is that the mechanics really kind of drive it. But if the mechanics feel disconnected, it's just this pretty thing. It's just an abstract.

Generally, we wanted to have a kind of feeling that, as a kid, you can't really make your own decisions in a lot of places. We also wanted adults to be a kind of obstacle or result of failure, right? If you fail a roll, the guards might find you and take you home to your annoyed parents. The kids should feel adrift in a sea of adult decisions.

How did you tap into that mindset and also access your own personal experiences growing up in that part of Sweden?

It's actually kind of weird, but taking walks in the woods. During design, I thought, how do I even emulate the kind of feeling when you're a kid? I can't just bike around the neighbourhood and do ping pong bash on people's doors and steal apples. That would be weird. Instead, I took a walk in the woods. You follow trails, crash through the wilderness, find a bit of a big stick and punch a tree or something. [laughs] That kind of helped to get into that adventure spirit, which I guess is like the method acting of board game design. But it actually worked!